Psychoanalysis and Wine.

According to my students, the most effective explanation I have given for lines of action of psychoanalytic interpretation is by analogy to wine interpretation.

Psychoanalysis is the form of psychotherapy where the centre of the patient’s problems is addressed by letting it manifest in the relationship to the doctor (Kohut, 1971). This ‘central problem’ may be conceived of as a developmental configuration of psychological arrest: a point in childhood where the responses from our parents were less optimal than we would have needed to flourish psychologically. This developmental configuration repeats itself in the relationship with the therapist, ‘in the background’ so to say, until the analyst speaks to it, bringing it into the foreground. And while some therapists might attempt to correct the parents’ shortcomings in their responsiveness to the patient, psychoanalysis defines itself by (the addition of) understanding this pattern, above complicit reenactment of a childhood scene (Freud, 1914). In other words, psychoanalytic understanding in depth is achieved by interpretation; the preference for talking, rather than behaving, in response to what’s being recreated from the past (Kohut, 1984).

Psychoanalysis is defined by some as the therapy of this interpretation (meta-comment) on the childhood reenactments (Gill). The interpretation is meant to shift conscious awareness from within the issue to without the issue, thus creating a new vantage point. Early Freud told us that he felt that interpretation offers the patient relief, as a significant temporary therapeutic effect. This relief is akin to the difference between being in a ship lost at sea in a storm, and standing in an art gallery looking at a painting of a ship lost at sea in a storm (Symington). On the other hand, the enduring therapeutic effect of interpretation includes i) bringing the emotional turmoil into loving contact with other, self-reflective aspects of the personality (Kohut, 1971) and ii) the growth-stimulating effect of the unique tension between a) feeling understood about your unmet childhood needs and b) feeling the frustration of those needs having gone unmet, as they are repeated in the present day therapeutic situation (Kohut, 1984). These enduring therapeutic effects are those of words transforming emotions and the internal, emotional world.

The meta-cognition is achieved via language in order to heal an emotional wound. That is, psychoanalysts listen, usually for a long time, and finally put into words something that’s already going on for the patient emotionally. This brings new awareness for the patient to that emotional experience, in a new area or in a new way. Analysts have worried and disagreed over exactly how the interpretation, a verbal statement, effects any kind of lasting psychological change. For example, books are full of verbal statements, but a book (alone) doesn’t usually cure emotional problems. One perspective argues that the verbal interpretation is not curative in itself, but rather catalytic; it is not the communicated meaning of the words chosen that do the real healing, but rather it is the emotional side-effect of having had those words spoken to you at decisive moments in the course of a long psychoanalytic treatment. This emotional side-effect can be a complicated phenomenon to describe.

But we are also obliged to explain how interpretation is different from the defence of intellectualisation, which is a mental technique for avoiding unpleasant feelings by shifting awareness to an intellectual stratum. The curative effect of interpretation should be something different from that defensive manoeuvre. The sign that interpretive therapy is not intellectualisation is found when the mental contents/concepts of the interpretation can ultimately be discarded and forgotten, without loss of therapeutic improvement, much like a bandaid can be discarded once the actual wound is healed. For example, if a patient’s anxiety disorder is the product of unconscious conflict over libidinal impulses, we would expect that interpreting (and exploring) this conflict as a cause of the anxiety symptoms would ultimately cure those symptoms. We would also expect this cure to be stable over time: If the patient had to keep ‘managing’ her anxiety symptoms with ‘strategies’ like repeating specific sentences to herself about the unconscious cause of her anxiety, we would start to doubt whether anything curative had taken place. The treatment doesn’t work if you need boosters forever (cf. Beck et al., 1979). The catalyst of interpretation needs to lead to change in enduring psychological functions (i.e., structure); it’s the change in psychological functioning without the need to retain the mental concepts that demonstrates true effectiveness.

The link in the curative chain between verbal interpretation and stable changes in subjective experience fascinates me. It had been difficult for me to describe without using much jargon, until I had a particular experience with a friend over a bottle of wine.

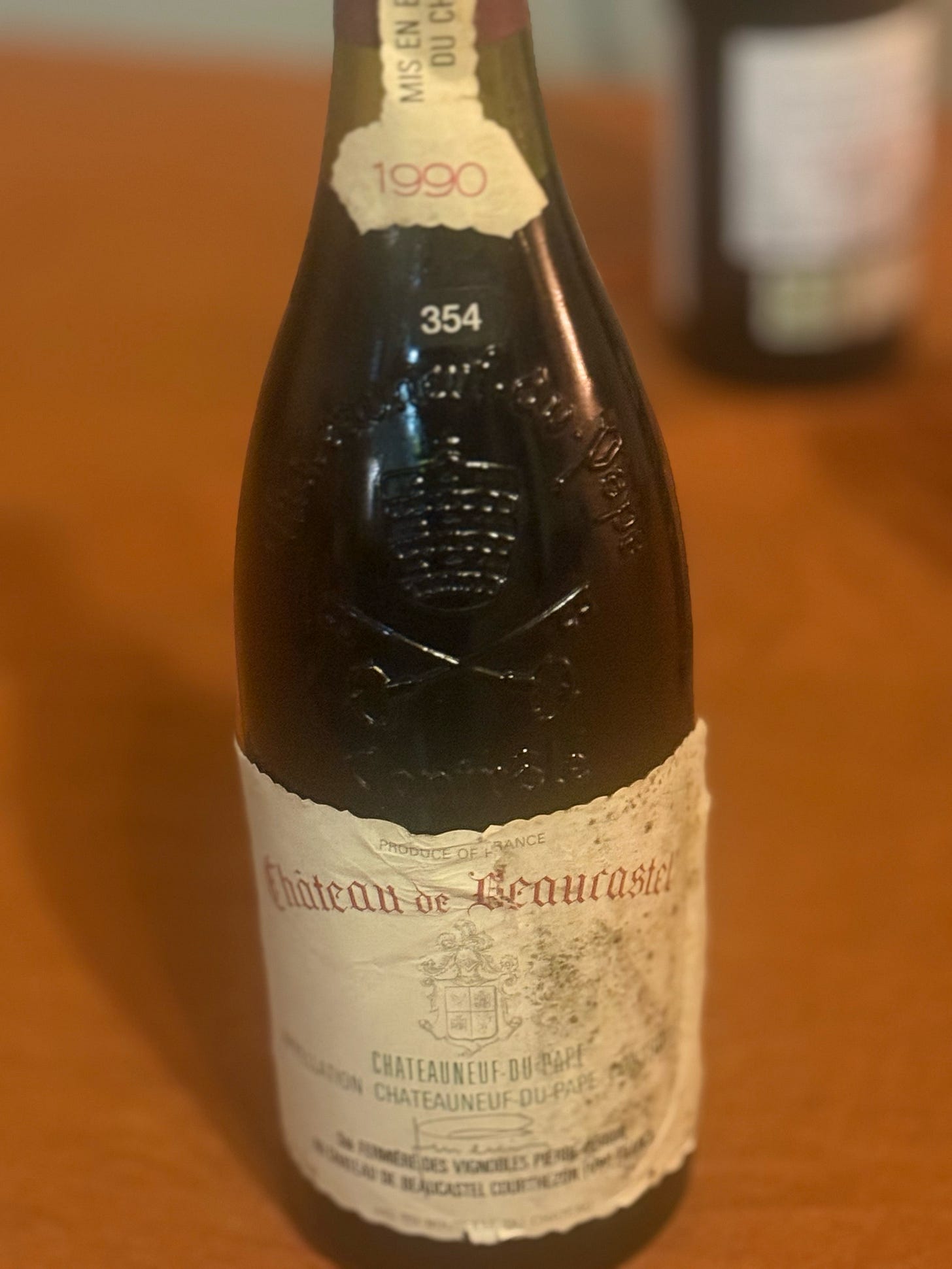

We were recently drinking a bottle of Châteauneuf-du-pape, when the essence of this catalytic function of interpretation was brought home to me in a new way. We were identifying aromas across the trajectory of the palette, when I told her I could taste peanut shell in the middle, hovering above the transition between the fruit and the finish. She reacted with wide-eyed surprise, precisely because she could recognise the flavour of peanut shell only after I had said the words ‘peanut shell’. She didn’t taste it before I spoke; but she tasted it after I spoke. I mean to pause over the fact that my words could not have added peanut shell to the wine but spoke to something that had been equally present, yet not available in conscious awareness, in every previous sip. The subjective experience was altered by the words (which are purely arbitrary symbols for the actual aroma): the very same wine tasted different in that moment, and from that moment forward. What was true all along became known only after the speech act. And what became known and experienced was, not by accident, something richer than before.

It took words to make the flavour noticeable for the first time, but the flavour itself remained in awareness after the words fell to silence. That flavour cannot be confused with the words that name it. This was a clear example of words permanently altering direct subjective experience, in this catalytic manner: First there was one subjective experience, then words were added, then finally the subjective experience (of the same sensation) was altered. In the psychoanalytic example, the true curative function depends on the words themselves becoming irrelevant over time. The patient’s new healed subjective experience of himself and his life should outlive the words that got him there. Again: If repeated antidoting with verbal self-medication is permanently required, then the subjective experience itself has clearly not been altered.

If our verbalisations in psychoanalysis were primarily transformative because of their content, it would suggest the that the cure is about our patients ‘learning’ something that they would ‘remember’ after the therapy ends. (By contrast, a friend and colleague once told me that after his years-long [curative] analysis, he could not remember his analyst’s name.) While I think many patients who achieve therapeutic cure may well think afterwards of things said in treatment, that does not demonstrate conclusively that the memory of utterances is perpetuating the therapeutic change, by micro-dosing. Instead, I hope for my patients that whatever I say to them over the years we work together, by the end they can afford to forget everything, while the taste of wine will forever be richer.